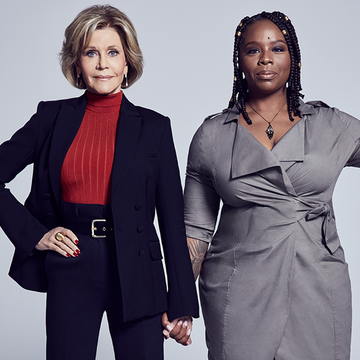

For our 2019 Women Who Dare series, activist and academic Rachel Cargle takes us into the weeds of America's systems of oppression with womanist scholar EbonyJanice Moore. What does it really mean to be an intersectional feminist? And how do capitalism, class domination, and gender play a role in dismantling racism? One thing is clear: The liberation of black women depends on their ability to rest.

EbonyJanice Moore: When we talk about dismantling white feminism, I automatically think about Dr. Delores Williams, a womanist theologian who is having eco-womanist conversations. Basically, she talks about how black women exist inside this very unique space, being the only human beings to be used for both reproduction and labor. She's making this comparison with black women and the earth. There are no other human beings who have been used for both reproduction and labor. It's not just, "Do this work, do this work, do this work," but also, "Make babies to give back to this industry."

Rachel Cargle: Right, to do even more work. I recently had lunch with Dr. Chelsea Frazier, who is an art literature critic doing her work at the intersection of black feminism and ecology. I'm really excited for her work, as she is breaking down some of the ideas that keep us from centering black women and femmes in conversations of ecology and environment. One of the things that comes to mind around this conversation of dismantling are the ways these big concepts have been turned into buzzwords—white feminism, intersectionality, capitalism, gender—and it makes me think about the true definition of these words and how alone, they are often skewed, putting us in a space of frustration and confusion. A lot of people don't even really know the definitions or the backgrounds of these very basic structures, of each of these movements, and especially with intersectionality, it's like a badge. It's a buzzword and a badge to say, "I'm an intersectional feminist," or, "We're an intersectional organization," or something like that.

But people don't even get to the root of, not only understanding the word, but understanding everything behind the word. A lot of intensive theories and study went into us being able to even have these critical conversations around intersectionality, feminism, or capitalism. All these systems are so woven within us. Especially hearing students in these conversations, bringing things up that they might not have a grasp on the proper definition around it in the first place.

EbonyJanice: Oh, yeah. Don't get me started talking about the things that my students don't know the origins of. Intersectionality is such a perfect buzzword in that people, exactly what you said, people use this title and they have no clue of one) where it came from, and two) even then, Kimberlé Crenshaw herself has talked about the fact that before she coined that phrase, this work was already happening, that people were already having conversations about the intersection of race and feminism. Or race and gender.

Rachel: And many don't understand that it's not just like, "Oh, someone wrote about it, a few years ago." Like, no, these are generations' worth of people who have been doing critical intersectional work, specifically around the exact things that Kimberlé Crenshaw talks about. So she's citing and acknowledging the history of the theory, but a lot of people who are using the term, their understanding doesn't go further back than a few years of study.

EbonyJanice: The other thing that I was thinking about in regards to all these terms is how often people come in and they co-opt them. And then they completely whitewash it. So you have this idea that's super rooted in blackness and femininity, and then, now all of a sudden, you can talk about it and not ever bring up black women. How is that possible?

Rachel: Exactly.

EbonyJanice: Additionally, I don't know if you've ever read this article by Angela Davis, "The Black Woman's Role in the Community of Slaves," where she's literally breaking down where a lot of the stereotypes of the matriarch came from, for black women. And ultimately, that whole article is talking about intersectionality in and of itself—what black women were doing to subvert. There was no room for femininity for them, because then they also still had to go be in the field. The gender and race thing was always an issue, period.

Rachel: I want to talk about the reality of the various systems of oppression, whether we're looking at gender or race or class. What spaces have you been in, whether it's in the academic space or even just in the people who are existing under these systems of oppression, when you're having conversations? Kind of the back-and-forth between, do you dismantle the system from inside or outside? Especially with it being voting season, there are [social media] posts that say things like, "Vote to dismantle the system, through the system," and then other people are like, "Forget voting, we need a whole new system if we really want justice!"

EbonyJanice: I have been seeing and having this conversation, of course, but I worry about being the appropriate person to be having this particular conversation with. Because I do have some Garveyite kind of ideas around what it looks like to actually dismantle the system. I don't think that you can really fix a thing that has always been broken. How is that possible?

Rachel: Exactly, what are we restoring it to?

EbonyJanice: Exactly. There is nothing that could ever be good from this, period, so we have to create a completely different system. And for black people, for people of color, but with emphasis in the U.S. for black people, I personally feel like that might look like not this system at all.

Voting is very important, our ancestors died for the right to vote. But what does it look like for us to vote because we're, we actually are in support of this? Like in Harlem for example, which is very decidedly black still, in New York City, they're voting on this resolution that will ultimately tear down [the housing complex] Lenox Terrace. If they tore down Lenox Terrace, people will be displaced, and they'll build this high-rise that will end up being higher than the hospital over there. The 2 and 3 subway line is already the most overcrowded. Race and class play a part in the decisions that are being made. So vote for those kinds of conversations, but not necessarily just because of your Grandmama, but because you are being active in your own right.

Rachel: I want to talk about the irrationality of billionaires and the intersection of capitalism into the other conversations around social justice. I feel we don't always bring capitalism into our social justice space conversations, particularly on social media.

EbonyJanice: Yeah. That's a very easy conversation, though, because we could just talk about black billionaires.

Rachel: That's the exact intersection that I'm referring to.

EbonyJanice: Like, if black men are striving towards this idea to get money, what is their comparison? This is where the conversation about classism comes into play. There is so much push even in oppressed communities about "making it in America," and in reality, our ultimate measure of success with that thinking is rich, white men. The idea of us pushing to be the next black Bill Gates just doesn't track.

Rachel: Bill Gates, oh, yeah, that's a good conversation. We don't want to be Bill Gates.

EbonyJanice: It's a critique of the messaging that has been put forth specifically by white men. This is the American dream: You get money, get money, get money. We live in this capitalist system. Many people have bought into the idea that this is an ideal system we live in. This is the way that we can compete. And this conversation is in relationship with intersectional feminism, because we must consider who will be doing a majority of the labor to even get those people their billions? History has shown us that it will most likely be on the backs of black women. These billionaires, including black billionaires, [get their wealth] on the backs of black laborers, or people of color.

Rachel: Right, because they're in a system that was developed that way by white men. They're not becoming billionaires off of anything else than what white billionaires are becoming billionaires off of.

EbonyJanice: It goes back to what I was saying about Dr. Dolores Williams making that comparison of these bodies being subjugated for both labor and reproduction. You keep on bringing people more people—you know, having more babies, having more children, more people of color—you keep on bringing them into this system that is going to create a story for them: You can have this American dream if you work hard. There is this woman who's always at the McDonald's on the corner of 132nd and Lennox, she's always there. She's a hard worker. She's never going to be a billionaire.

Rachel: Right, exactly.

EbonyJanice: She's a woman of color. It just continues to show you how intersectionality, this idea of bringing in gender, race, and class all into one conversation, they cannot be separated.

Rachel: It cannot be separated.

EbonyJanice: I feel like the major role that I'm playing in this revolution, if that's what we'll call it, is what does it look like for us to actually center black women? Which is womanist work in general. Womanism is this sociopolitical tool that centers black women in every conversation, particularly because black women have been excluded. And so, if we center black women in every conversation, what does it look like for us to center black women in a conversation about pleasure, and joy, and play? I have been asking my closest friends, including you, if you could dream yourself into your highest reality, would you be doing this work right now? Marching to Selma, would you be doing this? And 99.999 percent of the women said, "Hell, no. Hell no, I wouldn't be doing this work. I would be doing something else." So it's just the very idea that black women don't even particularly get to dream themselves free for real, for real, because we're so busy fighting … everything.

Rachel: Fighting the system. I think about that a lot. Who would we be if we weren't just trying to survive? But considering, you know, especially as me, someone who was a nanny of white children in particular, I helped raise them. To see some of the carefreeness that they experienced … to experience that, which I never have, and really don't often see, for black children.

For example, I had a friend who had posted on Facebook that she was pregnant, and everyone was so happy and so excited, they were writing all their congratulations. Then she DM'd me and said, "Rachel, I just wanted you to know that I found out I'm having a son. And as a black woman, all I've been doing is crying." And just considering moments like that where it should be joy, it should be celebration, it should be even perhaps the relief of something that she's been dreaming of happening all of a sudden coming true, it becomes a moment of mourning before anything has even happened. Like, he hasn't even been born yet, and she's already mourning what his existence will be like.

Now I think a lot about, whenever my black friends find out they're pregnant and they're having black boys, but also birthing a black female into the world is a terrifying thing, really giving them as much joy and celebration as I can to counteract the underlying fear that I know they have, even if they don't express it. So what can I do to counter that, or to do something to put them in a space of knowing that I'm going to try to give you at least a little bit of what you deserve? Even if the world hasn't.

EbonyJanice: Rachel, the idea of little black boys is literally where Dream Yourself Free came from. I'm listening to, on audiobook, Patrisse Khan-Cullors's When They Call You a Terrorist, and I'm thinking about this work that she's doing in the book at this point, building this space for her brother to be safe. And I thought, Oh, I need to do something like that for my nephews, my nine and 11-year-old nephews who were in this predominantly white school that just didn't know how to serve them, just didn't have the tools to serve them. And as I'm thinking it, I think, I don't have time to create another program. I don't have time to.

Then, I had the revelation that Patrisse is a noted artist, right? She's a celebrated artist, but all we know about her is Black Lives Matter. We don't know she's an artist. And you found out this summer that I am actually an incredible writer and a performer. Unfortunately, that's not how you met me; we met each other through this exhausting anti-racist work.

Rachel: Thinking of exhaustion also brings me back to my original question of us talking through what we do to fight back against systems, whether it's within ourselves, or our community, and it's never easy, but giving myself permission to rest. For a time, I felt that surviving as a black woman was my job. Not being a writer, not being able to develop meaningful stuff. And so resting, writing for fun, just writing a silly story, or just reading a novel instead of going through and feeling like I need to read every race book that's ever been written so I feel more equipped to exist in the world. I just want to read books about puppies, and flowers, and sunsets. I could ask probably any of our close friends about what they're reading, and I guarantee you everyone would have an academic book in their backpack.

EbonyJanice: Some critical race theory, not some thug passion or something.

Rachel: A very frilly book would be so wonderful to just lie back and read. But it feels like it's wasted time when we're not fighting for our lives and the lives of the people in our community. I think about The Nap Ministry and the work that they're doing around pushing us to rest and pushing us to think more critically about the ideas of rest and work, capitalism, and class. They're real intersectional over there, looking at rest from a critical standpoint, which is so wild that we have to be sitting here thinking about rest critically to find value in it, because it's just not a part of what we understand as black women.

EbonyJanice: What you just said is so real, especially about that particular organization, because people think it's a joke. Her name is Tricia Hersey-Patrick, and she's literally deconstructing how class and racism is impacting people's ability to take a break.

Rachel: Literally, doing the deepest work.

EbonyJanice: The deepest work, and y'all think this is a joke. But because it goes again into what we were talking about [the American Dream of] working hard. You know, you got to be a hard worker! No, no, no, go take a nap. Go to sleep. Rest yourself.

For me, one of the major things that drew me to the work that you're doing is I love seeing you chilling. There is something so revolutionary about seeing a black woman chilling, sitting on the beach, talking about, "Hey, y'all, it's your girl, Rachel." The fact that rest is revolutionary in 2019 is actually just mind-blowing, but it's so real.

Rachel: It speaks to those intersections of who I am, who we are as black women. I grew up very poor. I had this understanding that if I hustled a certain amount, that it would give me everything they said it would.

EbonyJanice: But to go deeper in that, the reason why you even have language for that, though, is because you've been doing the work of rest, because there is a point that you've been working so hard, working so hard, working so hard that you don't even know that you're suffering from anxiety. You don't even know.

These are just basic ways that black and brown people are showing up, as a result of being overworked and underpaid on a regular basis. My dad is a 60-year-old black man from Meridian, Mississippi. Right now, if my dad walked past my bedroom door and saw me just sitting here, chilling, he would be like, "Why you ain't doing nothing?" Yes. "It's 7 p.m. What am I supposed to be doing?" But it's this history from slavery. You've got to keep moving. You've got to keep doing something, and people don't … when I think about The Nap Ministry, that's the critical work that she's doing of, like, "Let me help you understand the origin of why people of color don't know how to sit down somewhere and be still." This is a very real thing.

Rachel: And feeling like our value—and this is capitalism here—is rooted in our production. I think about our babies in kindergarten. Talking about decolonizing play, not just for us as adults but also for our children, their understanding that they have to be continuously producing or competing in order to have value and that you can't just exist and be someone of worth.

EbonyJanice: It's so, so, so, so deep. If anything, I want to talk about what it really looks like for us to just be glorious, end of sentence. Even the idea of black excellence looks like a very specific thing.

Rachel: As I continue to move forward in my career, I've been considering how much money I actually need. I'm a single woman, essentially living by myself in New York City. I don't plan on having children. I am fairly low-maintenance in terms of I don't go clothes shopping and shoe shopping and jewelry shopping. That's just not really me, who I am. So how much money do I really need to be comfortable? I'm just fighting this capitalist idea that I need more and more and more.

I'm telling my accountant, "If I make more than this in a year, just put the overflow into my foundation, or just put the overflow into this foundation, or just put overflow into this homeless shelter," or whatever it is that I decide, because I really don't want to live my life feeling like I need to do more and more and more. I want to decide what is good for me and comfortable for me and just continue to do my work—not because I'm constantly trying to be in competition with my peers who are doing this work, or competition with anyone, or even the system. I'm here to do my work, and I'm doing my work, because I, at this point, still find joy in it and find deep purpose in it.

EbonyJanice: That is, again, very similar to the idea of rest as a revolutionary tool for people of marginalized identities. That, what you just said, it's so foreign that it absolutely is revolutionary as well—the ease of getting to a certain amount of money and then having this very serious question with yourself, being able to have a question with yourself about, "Will this be enough? What does this look like?" From an economic standpoint, particularly for marginalized communities, most specifically for black communities, black people have historically been very communal, which means that, as you're getting money, that money's not just for you.

Rachel: Right.

EbonyJanice: So you kind of can't put a cap on how much money you can make, because you're always thinking about, "And my mama, and my cousin, and the people on the street, and the school that I went to." That connection is very in relationship with the idea of rest, because you're giving yourself permission to not overwork.

Rachel: Really, it makes me so happy to think, I will continue to make money, but it just doesn't have to go to me. There are other things to take care of. There are other people to take care of. There's other community. There are other things, and me just buying a bigger apartment or buying a bigger car or buying more types of clothes, it just doesn't make any sense for me.

EbonyJanice: Which is what you said earlier, Rachel, about the fact that so much of what capitalism forces us to be thinking about is that our labor and our worth are in relationship with each other, and those things are the proof that you are worth. My Dream Yourself Free workbook came from a three-month workshop that I did specifically for black women to have conversations about what it would look like for us to dream ourselves free.

Executive Editorial Director: Joyann King | Photography: Allie Holloway | Chief Visual Content Director: Alix Campbell | Senior Visual Editor: Lauren Brown | Styling: Cassie Anderson | Stylist Assistant: Danielle Flum | Design Director: Perri Tomkiewicz | Designer: Ingrid Frahm | Digital Tech: Tim Mulcare | Photo Assistants: Matt Lamourt & Angela Cholmondeley | Director of Photography: Michael Sassano | Video Editor/Colorist: Erica Dillman | Makeup: Jaleesa Jaikaran at Management+Artists | Special Thanks to ROOT Studios