When Richard Avedon guest-edited the April 1965 edition of Harper’s Bazaar, the issue was billed as “a partial passport to the offbeat side of Now.” For the cover, he snapped the model of the moment, Jean “the Shrimp” Shrimpton, her face framed by a Day-Glo fuchsia cutout that evoked an astronaut’s helmet.

This April marks the 60th anniversary of Avedon’s celebrated issue, and we’ve taken many cues from it as inspiration for this one, which is dedicated to the idea of “now.” As in the 1965 issue, we gathered artists and writers, from Lorna Simpson to Torrey Peters, to fill the pages with their responses and reactions to these times.

One big difference between then and now is that today it would be impossible to identify a single face that defines the moment. If politics seem to be regressing to a pre-1965 era, at least the standard of beauty has changed. Where Shrimpton’s features—big, wide-set blue eyes, high cheekbones, light hair, light skin—were once considered the pinnacle of beauty, the definition now is mercifully broader, more encompassing and diverse.

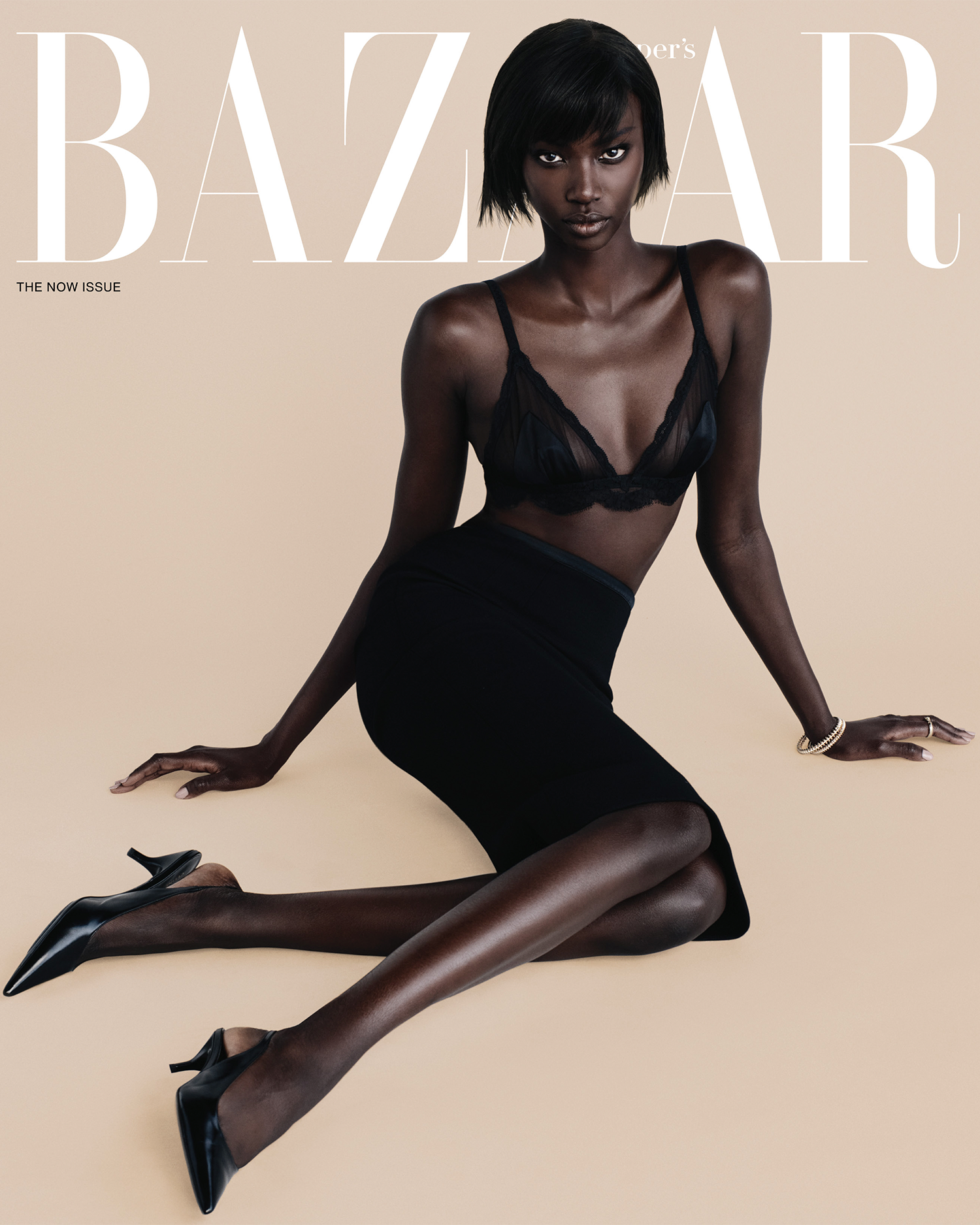

Take the models who grace the cover of this issue: Alex Consani, Anok Yai, and Paloma Elsesser. They each hail from different backgrounds, ethnicities, and communities, and all walk the most coveted runways, secure the biggest campaigns, and are featured in the glossiest magazines.

Yet even as recently as a decade or so ago, the landscape was drastically different.

“When I first started, the beauty standard was the opposite of who I am,” says Yai, who is 27. “I remember being on sets at the beginning of my career and seeing girls who didn’t look like me at all, and I knew that they were the standard. And I remember, in my head, deciding, ‘I’m going to force myself to be the standard.’ ”

Yai recalls the emotional and physical toll modeling took, particularly when it came to her hair. “I had naturally very long hair, and everyone was convinced that I was wearing a weave, so they would tug on it and do whatever,” she says. “I lost 10 inches of my hair six months into my career. I remember being on set and the hairstylist would ask me, ‘Do you know how to straighten your hair?’ And I would say no, because I’d never straightened my hair before. And then the hairstylist would say, ‘I don’t know either.’ So we would have to sit on YouTube and watch tutorials. This was the first year that I started modeling, so I was like, ‘I guess this is the new normal.’ But then I realized that I was coming onto sets with my own makeup, with my own hair products, while my counterparts just had to take showers and show up.”

As a response to the damage her hair had sustained, Yai decided to wear her hair in only an Afro or cornrows. It was a choice that helped change the look of the runway. She started doing it, she tells me, “one, to preserve my hair, and two, to enforce an acceptance of Black hair in the shows. I would go backstage and there would be signs saying, ‘Don’t touch Anok’s hair.’ And then other Black models would be like, ‘Oh, my God, how did you do that? I want to walk my show with cornrows too. I want to walk the show with an Afro too’ … and then it got to a point when a majority of the Black girls had an Afro or cornrows. And then I said, ‘Okay, I did my job.’ ”

In addition to expanding and shifting the standards of beauty, perhaps the other greatest change for models now versus then is that they have a voice. Models are no longer silent actors, tabula rasa to represent whatever is projected onto them. Across their social platforms, Consani, Yai, and Elsesser reach a combined following of nearly 10 million. Through these platforms, they can advocate for their communities and the causes they believe in and also simply be themselves in a more multidimensional way than models have been allowed to be in the past.

On the day of this photo shoot, news was trickling out that major hospitals had begun canceling gender-affirming care for trans youth. These actions were the result of just one of President Trump’s several executive orders targeting trans people. Others have mandated that there are only two genders and erased references to trans people and gender-affirming care across government websites.

You would never know that these violent, targeted attacks hovered in the background while watching Consani, who is trans, on set. Consani was ebullient, joking with her fellow models and dancing on the catering tables when she wasn’t posing. She was, as they say, a mood, bringing a sense of levity and playfulness to her work. It’s not that the news didn’t weigh heavily on her. “It’s scary to see the most politically powerful and the most wealthy people in the world directly targeting my community specifically and mostly targeting the kids that are helpless to any of this,” she says.

But Consani feels a deep responsibility to use her success and her massive platform (4.6 million follow her hilarious antics on TikTok alone) to represent her community without compromising who she is. “I think that it’s important to just be seen as human beings, because that’s what we are,” she says. “Being on such a major publication, that makes me very hopeful. Our government might not receive our identities or our differences as acceptable, but what sells, sells. And seeing people be themselves will always sell.”

Consani is just 21 but emanates a sense of self that is both beyond her years and hard-won. “I’ve always been surrounded by love,” she shares. “My parents recognized when I was happy. Parents know when their children are happy. And I was always happy when I was being given the space to be in my gender euphoria.” There is that foundation of family support, but there is also a toughness and fearlessness that comes when you experience hate crimes at six years old. “I knew I wasn’t going to be the only one that went through this, and I’m not going to allow other people to do this,” she says.

Elsesser, 32, has been modeling for a decade and is more pointed in her assessment of the current state of the fashion industry. She notes, “Obviously, there has been a decline” when it comes to size inclusivity, part of a larger “zeitgeist shift toward a sanitizing of humanity. I see humanity in the ways that people are different,” she continues. “I know that diversity and inclusion sounds like an eye roll at this point, but people forget its purpose.”

Elsesser often finds herself among the few—if only—curve models on a given runway or campaign. “There is a profound amount of responsibility and pressure to carry a conversation that’s not my responsibility,” she says. “It’s an industry responsibility.”

It is crucial to acknowledge the limits of representation and the unfair pressure it places on those who break through in spaces that had not previously allowed them in. It’s a sentiment that resonates with all three models.

“Do I think that representation melts away people’s self-hatred?” Elsesser muses rhetorically. Still, she admits there is some good that comes of it. “Do I find comfort and joy that maybe seeing me in a magazine or seeing me ‘thrive’ can bring just a moment of reprieve to someone? It’s not everything,” she says, “but it’s not nothing.”

Finding hope in a shifting industry grappling with its response to a chaotic and oppressive new administration is a tall order. Elsesser calls for more curiosity. “If we cultivate a culture of curiosity, hopefully things can change,” she says.

Where Elsesser is contemplative, Yai channels her frustrations and fears into her art. “Turbulence creates the best art,” she says, noting that she’s currently working on her fourth painting. “This is when all the best art comes out. I keep my head focused on the art.”

Consani is down to fight. “I like to be in the streets,” she says. “I like to do as much as I can. I speak publicly about what I believe in, and that makes me hopeful.” She explains, “I grew up online. I’ve been on the internet since I was eight or nine, so I’ve always gotten hate, and I’ve always known that it’s coming from a place of self-hatred, because no one takes time out of their day to go online and talk negatively about someone unless they have self-hatred within their own head. So I push through it by knowing that I am doing what I love and I’m being vocal about it. If you want to hate on me? Do it. Do it, because you know what that means? More clicks, more views, more money for me, babe.” Taking a more somber tone, Consani acknowledges, “Sometimes it can get you wrapped up in the negativity, when that’s never been what our community is about. It’s always been positive. …Even in the face of such negative policies, we’re able to recognize that us as a community can’t be affected. We’re never going to go away. We’re never going to go away.”

This article appears in the April issue of Harper’s Bazaar.

Hair: Jimmy Paul; makeup: Fara Homidi for Fara Homidi Beauty; manicures: Dawn Sterling for Dior; casting: Anita Bitton at the Establishment; production: Tann Services; set design: Marcs Goldberg.